Misunderstanding the Logic of War

Ukraine and the Will to Fight

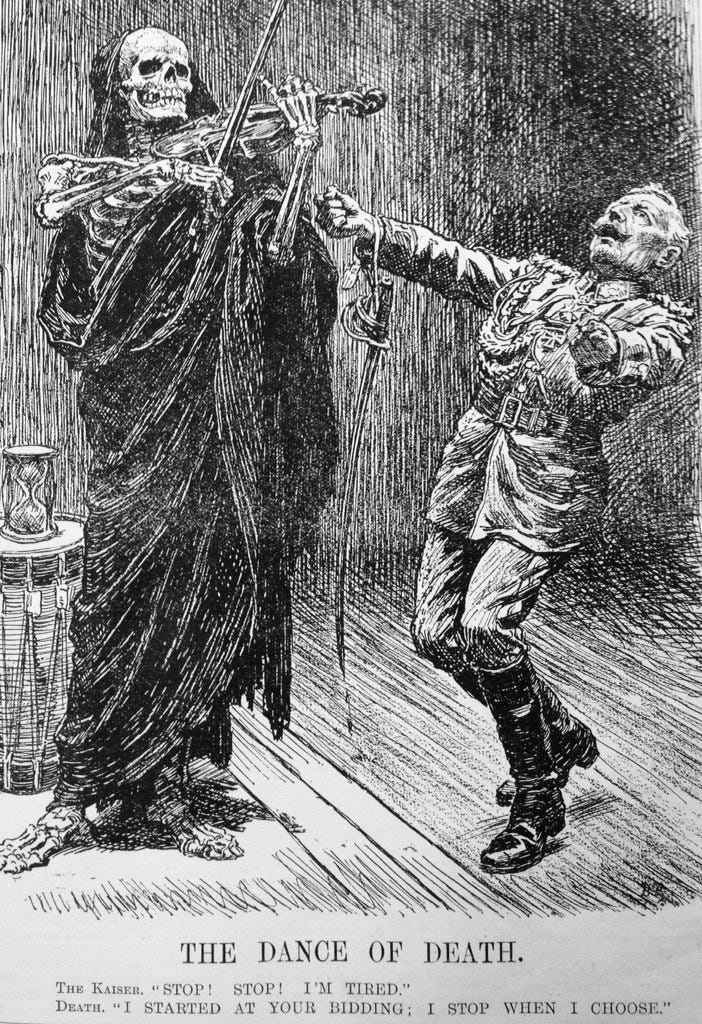

Punch Magazine, 1917

With the failure of the Ukrainian counteroffensive to reach its operational objectives in Zaporizhzhia before the onset of winter, the arguments for Ukraine to admit defeat have come back in force.

The argument goes something like this: Ukraine had one last chance to defeat Russia on the battlefield and conclude the war on favorable terms before Russian structural advantages in industrial capacity and manpower would fundamentally preclude any possibility of Ukraine’s victory. With the failure of the Ukrainian counteroffensive to achieve its operational goals, any further fighting would be a futile display that would senselessly cost lives for what is now a foregone conclusion.

Variations of this argument have a sort of inherent surface-level appeal. It makes an intuitive sense that of course, the State that has more tangible resources at its disposal will in fact prevail in any sort of extended conflict.

Books like The Allure of Battle and Wages of Destruction cover the importance of raw industrial productivity in the pursuit of war very clearly. If you’re more into sociological attempts to understand industrial war, I’d also suggest Ernst Jünger’s On Pain. They’re necessary correctives to dogmatic Clausewitzians who take the importance of the component of will in warfare alone too far.

Taken to extremes, however, it leads one to the idea that the outcome of any given war is nothing more than a teleological exercise in the calculation of assets and their expenditure over time like a strange form of financial accounting.

It should be pointed out here that Ukrainians do still have their own industrial base that has been—and will continue to—produce much-needed equipment for their war effort. It’s also worth pointing out that while the Zaporizhzhian offensive did not achieve Ukranian aims, losses in Ukrainian equipment have still been relatively minimal in an attritional context.

The United States and Europe of course can also continue to support Ukraine with arms and equipment for as long as the political will exists to do so. Support for Ukraine is a trivial matter in terms of GDP and military spending for these countries, and any issues with defense production are a matter of political will rather than any actual metaphysical limit on the ability to provide this support.

Which gets me to my point in writing this. Spending 10% of your GDP on your military is not the same thing as having soldiers who are willing to get up and out of a fighting position and close with an opposing force under fire. An industrial base can provide your force with all the tools, but a cause is what gives those who use these weapons the ability to actually fight.

War is—and I cannot stress this enough—first and foremost a political activity, and the actual logic of when a war ends is driven by the domestic will of a political community to prosecute the war. A war does not just simply end when it’s most convenient for one party to decide that the killing will stop. The Ukrainians get a vote.

What I mean here is that the Ukrainian people have a reason to fight. Their capitulation will mean that an autocratic nation that has committed itself to ethnically cleansing Ukraine will get its way—and the Ukrainian people will be subject to Russian rule. They have an existential cause worth fighting for, and there is no foreseeable reason why the failure of an offensive would change this.

In an attritional war of position winning a war is still just as much about industrial capacity as it is about the ability of one’s political community to maintain a firm belief in the legitimacy of their cause. The more uncomfortable aspect of a contemporary war of position is that a modern nation-state can mobilize its population and resources for war much longer than you would expect possible. Ukraine put simply can realistically functionally continue to fight this war indefinitely as long as the will exists to do so.

This is to say, the Ukrainian failure to succeed this time in Zaporizhzhia means approximately as much as when the Germans prevailed at the Battle of Mons in the First World War. It means nothing. A war does not simply end when one party decides it will.

The United States spent years sending diplomats to the Taliban with lofty pronouncements about how there was no “military solution” to the war in Afghanistan. The problem with that logic was always that a war does not become unwinnable when only one party decides that it is. The Taliban disagreed and kept fighting. The Government of Afghanistan fell.

Proponents of Ukraine striking a deal, because they have decided by some arbitrary measure that the war is no longer winnable, are a sort of funhouse mirror of the State Department officials that parroted this line years ago.

The will to fight is what determines the outcome of a war, and Ukraine’s ability to prosecute the war until its conclusion is a matter that their domestic population will determine. Not the outcome of any single operation. Ukraine can fight—and Ukraine can win—as long as Ukrainians believe in the cause they’re fighting for.